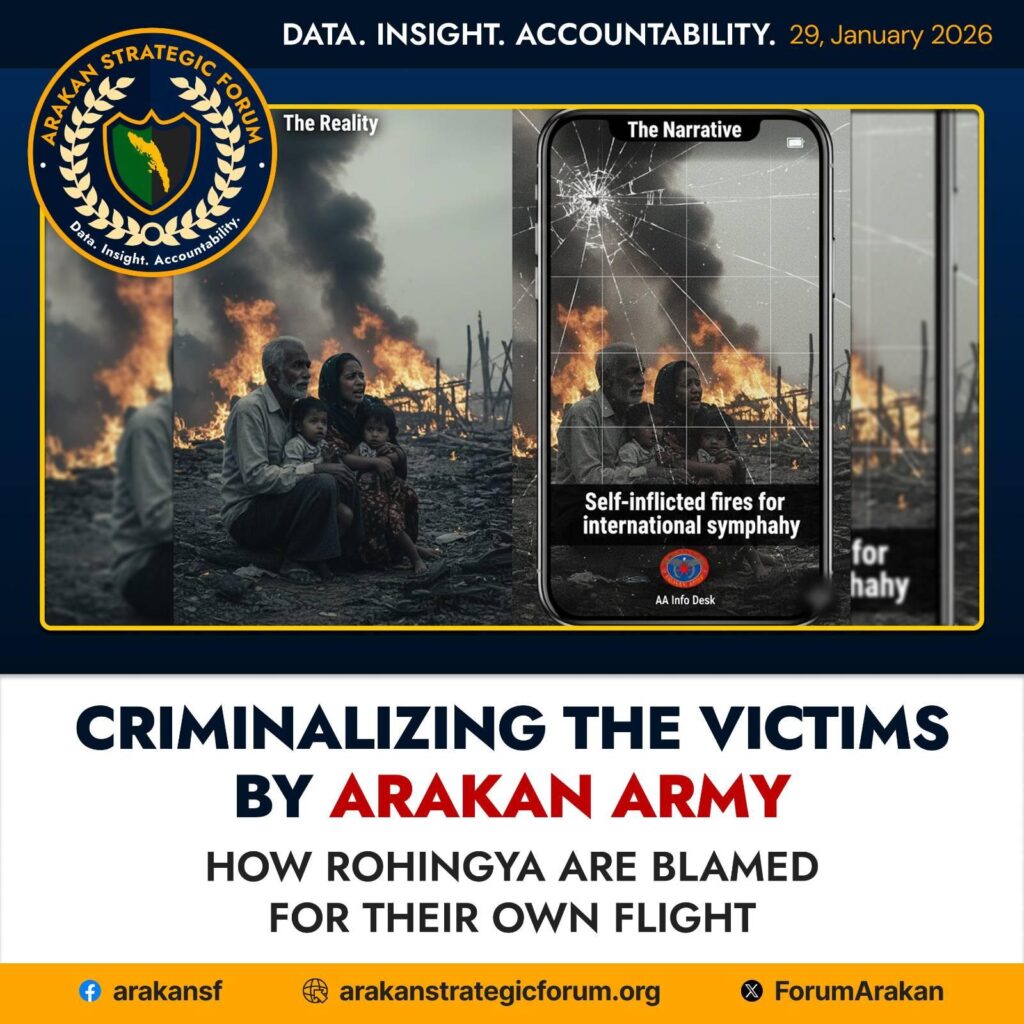

In northern Arakan, displacement of Rohingya Muslims is not treated as a humanitarian consequence of coercion and fear, but as proof of wrongdoing. Under the control of the Arakan Army, a consistent narrative has emerged in which Rohingya flight is framed as criminal behavior rather than civilian survival. This narrative inversion shifts responsibility away from the conditions that force people to flee and places blame squarely on those escaping them.

The logic is simple but effective: if Rohingya leave, they must be guilty. AA messaging circulated through local commanders, checkpoints, village announcements, and informal enforcement portrays departure as evidence of smuggling, disloyalty, or hidden collaboration. Civilians escaping forced labor, extortion, food restrictions, or land seizure are accused of “illegal movement,” while the coercive policies that made life unlivable are erased from the story. Flight becomes not a response to abuse, but a crime in itself.

This framing has real-world consequences. In Maungdaw and Buthidaung townships, Rohingya families facing daily labor quotas, arbitrary taxation, and farming or fishing bans are warned that leaving without authorization will result in punishment. Those intercepted on roads or waterways are routinely accused of smuggling or security violations, even when traveling with women, children, or the elderly. The burden of proof is reversed: Rohingya must justify why they are moving, while armed authority is never required to justify why they made movement impossible.

Several recent incidents illustrate this pattern. On 25 November, Bangladeshi authorities rescued 28 Rohingya women and children near Teknaf who were being smuggled by sea toward Malaysia. Rather than prompting scrutiny of conditions inside Arakan, this episode was framed in regional discourse as a case of “illegal migration.” Missing from that framing was the context reported by Rohingya communities: widespread food insecurity, blocked trade routes, confiscation of property based on fabricated complaints, and threats of expulsion for families unable to meet AA-imposed demands. The act of fleeing eclipsed the reasons for flight.

Earlier, in August 2024, reports emerged of civilians attempting to cross toward the Naf River amid intensified pressure inside northern Rakhine. Accounts of drone strikes and civilian deaths along flight routes were met with denial or silence from AA authorities. In the dominant narrative, those killed or displaced were not civilians fleeing danger but nameless figures outside the category of protected people. Criminalization thus extended even to the dead, further insulating perpetrators from scrutiny.

This narrative also facilitates economic exploitation. As legal avenues for movement are closed, escape is pushed into illicit channels by design. Smuggling networks charge Rohingya between hundreds of thousands and over a million kyats per person for dangerous crossings by river or sea. Once payment is made and flight occurs, the very act of fleeing is cited as confirmation of criminality. Pressure produces flight; flight is labeled crime; crime is used to justify further pressure. The cycle is self-reinforcing.

Language plays a central role in sustaining this system. By refusing to recognize the Rohingya as Rohingya and instead labeling them “Bengali” or generic “Muslims,” AA discourse strips those fleeing of legitimate identity. Without recognized identity, civilian status collapses. Criminal categories replace rights-bearing ones, and displacement is reframed as deviance rather than consequence.

The impact extends beyond Arakan. When Rohingya arrive in Bangladesh or are intercepted at sea, they carry the stigma imposed by the authority they fled. Host states encounter them already framed as offenders, not victims, increasing the likelihood of detention, pushbacks, or neglect. The original violence inside Arakan is obscured by layers of criminal labeling attached to those who survive it.

Criminalizing Rohingya flight is not an accident of conflict. It is a governance strategy that absolves those in power, deters others from leaving, and normalizes collective punishment by portraying an entire population as inherently suspect. Rohingya are not criminals for fleeing coercion and deprivation. They are civilians responding to a system that constrains survival and punishes escape. As long as flight is treated as guilt rather than consequence, responsibility will continue to be displaced onto the victims themselves—and the conditions forcing them to run will remain unchallenged.